What are the policy challenges for the implementation of living-lab-based open schooling in Europe? - OLD VERSION 2022Last update 20 Apr 202331 paragraphs, 64 comments

What are the policy challenges for the implementation of living-lab-based open schooling in Europe?Last update 20 Apr 202356 paragraphs, 4 comments

What are the policy challenges for the implementation of living-lab-based open schooling in Europe? - OLD VERSION 2022

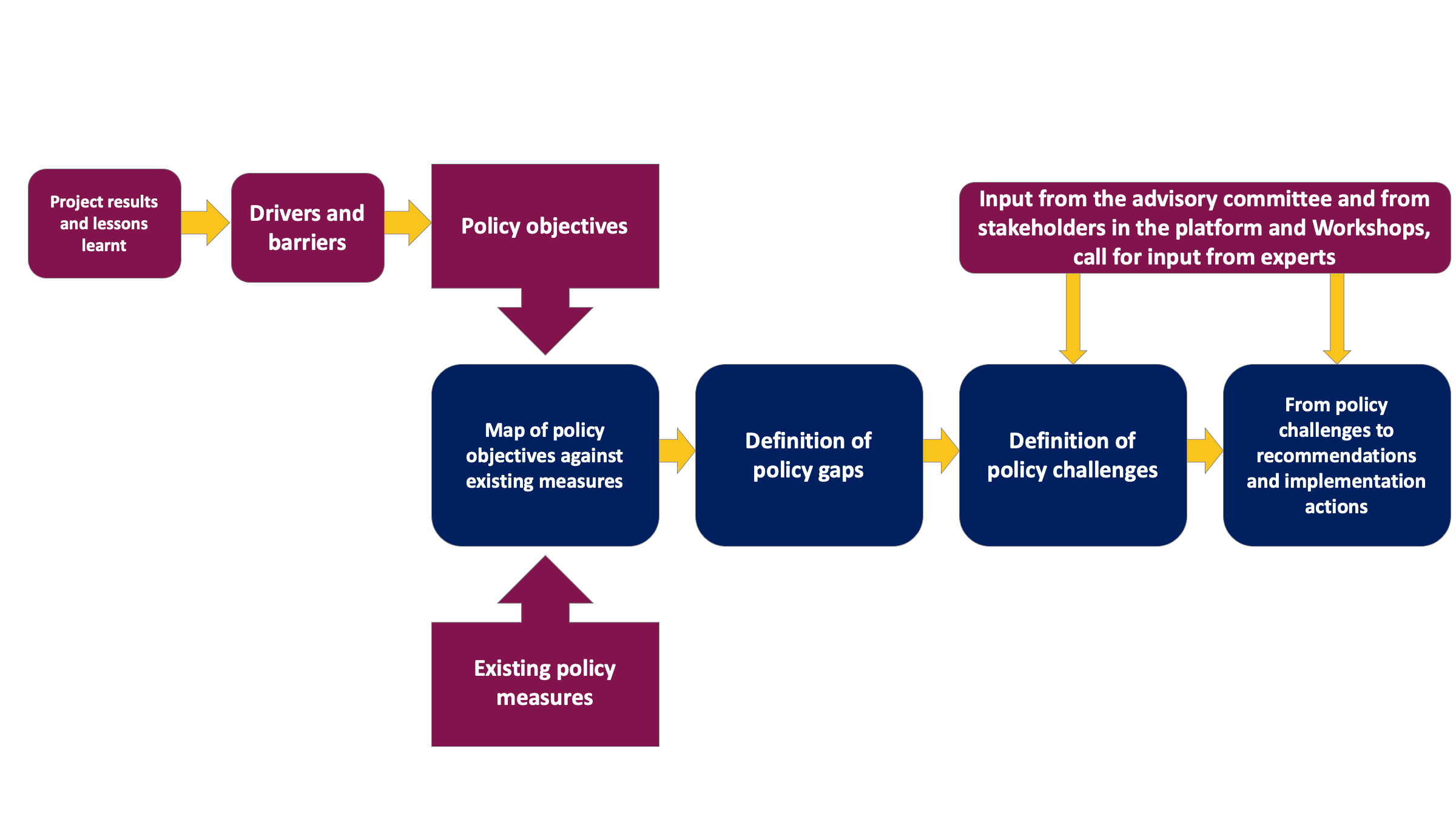

Methodology to produce the roadmap

First set of policy challenges in science education

* Disparity in basic science literacy. The 2015 Science Education for responsible citizenship report found that there is inconsistency in basic science literacy across Europe. According to the report, this is problematic because basic science literacy is required to ensure a thorough comprehension and application of scientific information in decision-making, notably in areas such as health, the environment, food, energy, and consumption. The report highlights wide discrepancies in science education participation, in formal, non-formal, and informal settings, across regions, cultures, and gender.

* Regional disparities. In terms of general educational achievement, there appears to be a North-South divide, with the highest rates of low-qualified people concentrated in southern Europe, particularly in Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Greece. The United Kingdom (UK), Belgium, the Netherlands, and Sweden, on the other hand, have the lowest rates of low-qualified people. The same trend can be observed in the results of the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). With regards to science performance the UK, Belgium, Netherlands, and Sweden rank significantly above the OECD average. Spain, Italy, and Greece rank below the OECD average.

* Gender gap. The latest PISA study also compared the performance of boys and girls in three key areas of education: reading, mathematics and science. The results show that boys scored higher in science and mathematics than their average across all courses in practically every country, while girls scored higher in reading. These distinctions may explain why boys are more likely than girls to pursue jobs in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) related subjects: students may pick their field of study based on comparative strengths rather than absolute strengths. Girls may be equally capable in science as boys, but they are more likely to excel in reading. The result is that girls and women make up less than 25% of students in engineering, manufacturing, construction, and information and communication technologies in more than two-thirds of educational systems. STEM careers, on the other hand, are in high demand and are required to address the world's current concerns, such as COVID-19, climate change, and food and water security. Gender disparities are particularly pronounced in some of the future's fastest-growing and highest-paying jobs, such as computer science and engineering.

By Vladimir Garkov (EU) - Across the EU, the gender differences in maths and science performance at the age of 15 are negligible. Furthermore, girls outperform boys in computer and information literacy in all Member States participating in the relevant survey.

highlight this |

hide for print

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:09

By Vladimir Garkov (EU) - Actually, boys underperform in science to a slightly greater extent than girls according to the PISA data (using the EU benchmark for underachievers).

highlight this |

hide for print

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:09

By Vladimir Garkov (EU) - PISA data indicate that both genders are equally interested in science careers (24-25 %).

highlight this |

hide for print

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:09

By Vladimir Garkov (EU) - However, there is a large difference in their chosen field of science. Girls tend to choose the bio-medical sciences while boys more often choose the physical sciences and computer technology. This may be related to the well-known phenomenon that women are naturally more interested in working with people while men prefer machines.

highlight this |

hide for print

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:09

By Vladimir Garkov (EU) - An important clarification: From an educational perspective, science and ICT are two distinctly different fields, even though ICT may be used as a helpful tool to promote maths and science teaching. Therefore, the EU key competences framework lists them as two separate key competences (STEM and digital): https://ec.europa.eu/education... .

highlight this |

hide for print

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:09

* Declining interest in science studies and related careers. In addition to the low numbers of girls interested in science, an overall declining interest in science studies and related jobs can be observed. This is problematic, as they are required to meet the demand for well-prepared graduates (at all levels) and researchers in our knowledge-based communities and economies. Both individuals and businesses are affected by this so-called "skills deficit." The average company spends more than $800,000 per year on recruiting suitable people. Recruiters' hiring pools are currently limited due to the present skills deficit. The most substantial skills gap among workers has been in the STEM industries. Additionally, a low interest in science studies and related careers contributes to the already existing lack of public awareness and understanding of the intricacies of humanity's scientific and social challenges, both in Europe and globally.

* Support system. Teachers and families play an important role in education. According to UNICEF, teachers and parents working together can help children better understand and overcome concerns and misconceptions, as well as boost community participation in addressing faced challenges.

* Lack of qualified teachers. The 2015 Science Education for responsible citizenship report points out that there is an inadequate understanding of the range of skills necessary of teachers and teacher educators in order to increase individual and collaborative accomplishment, innovation, and cultural and economic sustainability.

* Families and culture. Family involvement in children's learning has been shown to influence their achievement and success in school in research. The 2015 Science Education for responsible citizenship report stresses that family participation in education is required to pique children's curiosity, as well as a shift in emphasis from memorising facts to doing imaginative and pleasant things with knowledge, such as being creative with the application of ideas.

* Lack of cooperation. The 2015 Science Education for responsible citizenship report criticises inadequate investments in strategic collaboration and ecosystem development in science education. It suggests that more efforts in this field would promote effective adoption of the newest research findings and emerging technologies in industry and business, particularly SMEs. In addition to a lack of strategic collaboration and ecosystem development in science education, there is also too little involvement of stakeholders in science education policy, research, development and innovation.

* Monitoring. Finally, a remaining challenge in improving science education is the lack of strategies to analyse scientific education learning outcomes and the long-term impact of projects in many cultural contexts, and then interpret the findings for communal impact and benefit.

* Financial issues. Financial provisions for open schooling need to be designed in a sustainable way, and they need to ensure that open schooling activities do not create any extra financial burden for families. When implementing innovative programs, such as open schooling in the field of STE(A)M education, there is a need to differentiate between provisions for designing and setting up an innovative partnership and maintaining it. Successful open schooling initiatives are only possible in financing environments that provide funding not only for initial phases of such programs, but also consider and provide for the costs of sustaining it.

* Physical and legal Issues. Accessibility is a major factor in equitable education provisions. It is ensured by anticipating and mediating social/environmental barriers to enhance access for all learners. Open schooling has to be accessible for all students, and thus needs to be implemented with inclusion at the heart of activities. It is only possible if legislation supports such activities. While there is legislation in most countries on accessibility for disabled students, there are barriers, especially due to regulations regarding the organisation of school activities outside of the school or activities within the school that involve external people.

* Students' engagement. Disengagement because of boring and irrelevant experiences. The main approach will be to challenge and encourage students to explore themselves the notion of well-being by identifying and expressing what matters to them, what bothers them, what they can change or influence, how they can contribute or serve. Teachers should involve students in projects that are relevant to them and to the local communities to make them feel engaged and empowered, connecting classroom learning to real-life issues and settings in order to make it more meaningful for students.

* Digital divide/Access to technology. In today’s increasingly digital world, 3.6 billion people still have no access to the Internet. Those without access are typically the most vulnerable: minorities, people with disabilities, indigenous and marginalised groups, as well as women, children and youth from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds or living in areas affected by conflict and violence. Lack of Internet access reduces paths to a world of information available online, and limits the potential to learn and grow, all of which contribute to the digital divide. Today more than ever, there is a need to strengthen national infrastructure to ensure that connectivity is more widely available. Equally important is the need to strengthen school connectivity plans and to invest in quality learning in order to improve the educational access, learning outcomes and earning potential of young people, as well as the socio-economic development of their communities and countries.

* Rural Areas. Challenges facing students from rural areas who manage to reach high school tend to include: weak foundations laid in primary school; an unavailability of resources in their own languages; isolation and poor access to learning opportunities; digital divide and a lack of qualified teachers, particularly in Maths, Science, and English.

* Collaboration. Society, including learners at different educational levels, should be involved more in collaborative activities while collaboration is a key to success in today’s world and the collaboration skills need to be assessed and evaluated. Social skills in broad are a target in itself in the learning process, including science learning. These skills are a prerequisite for other activities planned to improve science learning and ensure sustainability of open science. Partnerships between teachers, students and stakeholders in science-related fields can offer exciting ways to introduce real life challenges, with their ethical and social issues, into a classroom setting while also aiding problem-solving skills.

* Lack of stakeholders’ commitment. Open schooling is often the only feasible alternative for increasing access to quality secondary education citing its flexible and indiscriminate enrolment system which offers opportunity to a wide range of individual needs. From this study conducted in Malawi, it emerged that the lack of stakeholder’s commitment to open schools is evident in the way open schools are established and organised which largely focuses on income generation for teachers rather than as an alternative route for increasing access to quality secondary education. This results in overcrowded classes which makes facilitation, assessment and other learner support systems difficult to provide. Even teachers’ participation in the open schools largely depend on the finances generated as some choose not to facilitate in the open school if they see that funds are not enough. The implication of this is the increase of cases of teachers teaching the subjects which they are not qualified to teach which in turn negatively affects open school learners’ performance.

* Evaluation issues. Evaluation is key to improving the overall quality of out-of-school STEM programs and to understanding how they contribute to the learning ecosystem. Evaluation can inform programme developers, researchers, policy-makers, and the public as to what out-of-school STEM programs contribute to interest and learning. They can also provide information about the broader context of STEM learning in a community. A critical issue in evaluating out-of-school STEM programmes is that learning occurs in diverse and unpredictable ways. There are many additional challenges to evaluating STEM learning in out-of-school programmes. Importantly, young people participate in out-of-school programmes based on their interests and motivations and use programme resources in different ways. Because of this, out-of-school programme evaluators have little control over who participates in a programme, which can make it difficult to know whether the outcomes of the evaluation could be replicated with different participants.

Do you agree with this set of policy challenge?

Do you want to add any other?

Do you want to merge any category?

Do you want to add any policy gap?

Do you think that they cover the entire spectrum of the problem?

What are the main features of open schooling

Please add your ideas

First policy dialogue: work on a real problem, relevant for the local community, to find and implement a real solution

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:11

First policy dialogue: co-create with stakeholders and societal actors in the local community

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:16

First policy dialogue: open to collaboration

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:16

First policy dialogue: ultimate goal is to benefit/broaden the mind of the students

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:17

First policy dialogue: mutual learning, listening

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:17

First policy dialogue: open minded participants

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:17

First policy dialogue: 'bottom-up' approach

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:17

First policy dialogue: creating conditions for cooperation between teachers of different specialties, who are involved in the study of the problem from real life.

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:17

First policy dialogue: open to the world and to learning from others

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:17

First policy dialogue: focus on soft skills and critical sense

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:17

First policy dialogue: open schooling: learn from collaborators, colleagues, students, experts

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:17

First policy dialogue: critical to create trust among all parts

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:18

First policy dialogue: we need a good way to define open schooling. The current concept is too broad to be actionable. Everyone can claim to be doing it. How do you recognize genuine openness?

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:18

What are the policy measures that should exist to foster the implementation of open schooling?

Please add your ideas

First policy dialogue: incentives for teachers

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:40

First policy dialogue: provide incentives for school management to implement the openness

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:40

First policy dialogue: work on teachers' incentives

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:40

First policy dialogue: ease up responsibility for teachers (so they feel safe into proposing innovative project involving partners, stakeholders etc... to interact with students, go outside the school etc.)

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:40

First policy dialogue: give teachers the opportunity to be themselves

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:40

First policy dialogue: give directions and freedom at the same time listen to them

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:41

First policy dialogue: teacher leadership roles need to be acknowledged and developed/supported

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:41

First policy dialogue: autonomy of teachers

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:41

First policy dialogue: flexible curriculum and autonomy of centre

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:41

First policy dialogue: flexible curriculum

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:41

First policy dialogue: school autonomy

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:41

First policy dialogue: novel approaches to leadership and governance; guiding by example, focus on enabling rather than governing

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:41

First policy dialogue: quality measurement (builds critical thinking, creativity, agency towards the future), not quantity- and solutions-driven only

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:41

First policy dialogue: supportive evaluation framework

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:42

First policy dialogue: the educational system is still linking educational success to school grades, not giving much room to creativity, critical thinking, etc.

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:42

First policy dialogue: funding

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:42

First policy dialogue: first and foremost ensuring good political will

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:42

First policy dialogue: common interest to change education system, not only particular interests

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:42

First policy dialogue: *orchestrated* multistakeholder collaboration - it takes organisation, it will not happen automatically ("freedom within framework")

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:42

First policy dialogue: policy change needed: open schooling "on top" of usual practise vs. real innovation

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:42

First policy dialogue: problem: how to foster cross-sectoral approaches if different legal and policy frameworks apply to these sectors (eg. funding)

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:43

First policy dialogue: provide resources for collaboration and orchestration

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:43

First policy dialogue: time and support for teachers to be able to spend time on this. Too often all great initiatives are all placed on the shoulders of teachers

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:43

First policy dialogue: agency creation: more focus on creating open spaces and mindsets for transformative learning and action

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:43

First policy dialogue: clear views on priorities across stakeholders

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:43

First policy dialogue: networks and growing communities

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:43

What are the gaps that should be considered and addressed for mainstreaming the implementation of open schooling?

Please add your ideas

First policy dialogue: teachers are the drivers for change, but they need support from within school (their Snr Leadership Team / Head Teacher), and local authorities and National levels

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:44

First policy dialogue: TIME / resources for thinking, unlearning, exploration

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:44

First policy dialogue: supporting leadership development, adult development.

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:44

First policy dialogue: changing culture of an organization takes time

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:44

First policy dialogue: a sustainable approach in terms of teacher's time and school financial system

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:44

First policy dialogue: organize teachers' training on how to work and collaborate in the open schooling system.

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:44

First policy dialogue: institutional support to place open schooling as a strategic educational approach and not only and exception or something casual

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:44

First policy dialogue: include it in the curricula at the national level, and not only as specific initiatives coming from schools only

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:45

First policy dialogue: central policy / curriculum / etc must recognise open schooling approaches as legitimate and mainstream, not as nice ideas and isolated one-off showcases

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:45

First policy dialogue: real innovation in teaching vs. formal requirements of the lesson plans "on top" approaches vs. integral approaches in learning and teaching

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:45

First policy dialogue: open Schooling is not known/not a mainstream in many countries - foster this direction of education in Europe and worldwide.

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:45

First policy dialogue: pan-European Collaboration and harmonized protocols for collaboration as a starting point will help the mainstreaming

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:45

First policy dialogue: collaboration among diverse schools and stakeholders from day 1 creates better understanding about the diverse needs therefore adoption and mainstreaming will be easier.

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:45

First policy dialogue: different cultures, different levels of experiences, different languages among involved stakeholders

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:45

First policy dialogue: teacher training

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:45

First policy dialogue: changes in access to universities

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:46

First policy dialogue: each country policy takes under consideration the possibilities and weaknesses of school communities

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:46

First policy dialogue: lack of cooperation culture

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:46

First policy dialogue: innovative assessment methods

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:46

First policy dialogue: regarding Roma education, it is important to perceive Roma children as capable of integrated open education and to take into account successful school integration practices in different countries.

highlight this |

Francesco Mureddu

- 01 Oct 2021 19:46